Heat distress can lead to heat stroke, this is more common in poorly ventilated or coops that are either too small or over crowded. Here are some guidelines for both treatment and prevention of heat distress in chickens. Don’t bring your chickens indoors where it’s cooler, this will make it difficult for your birds to acclimate when returned to the coop. Move them to a shaded area and follow these steps listed below.

What Are The Signs of Heat Distress?

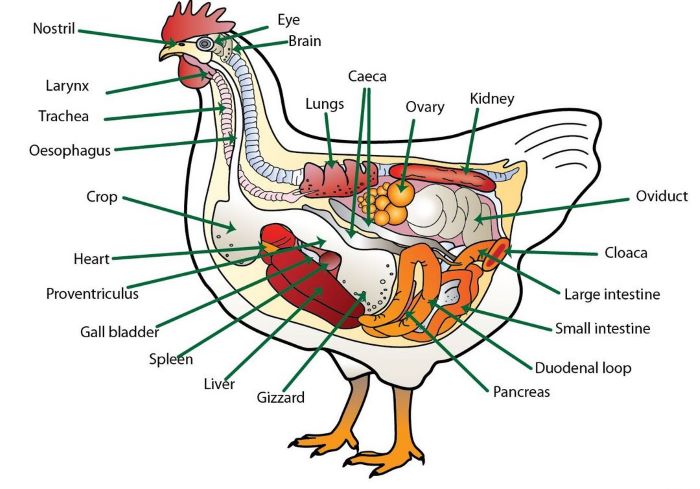

Panting: Chickens will often pant to try to cool themselves down when they are overheated. This is a common and visible sign of heat stress.

Wings drooping: When chickens are too hot, they may spread their wings away from their bodies in an attempt to release heat.

Lethargy: Heat-stressed chickens may appear lethargic and less active than usual. They may sit or lie down more frequently.

Pale comb and wattles: The comb and wattles of a chicken may appear pale or discolored during heat stress.

Diarrhea: Heat-stressed chickens may have loose or watery droppings.

Treating Heat Distress

Provide access to cool water: Offer the affected chicken cool, (not cold) water to drink. You can add electrolytes to the water to help with rehydration. This is available at any feed store.

Spray or soak the chicken with water: Lightly spraying or gently soaking the chicken with cool/warm water can help lower its body temperature. Do not submerge the bird in cold water, this can lead to shock.

Use fans or air circulation: If possible, set up fans or improve ventilation in the coop to reduce the temperature.

Use Shade Cloth: Never use tarps where birds are housed, they inhibit ventilation.

How to Avoid Heat Distress

Avoid overcrowding: Overcrowding can lead to increased body heat generation. Provide enough space for chickens to move around comfortably.

Limit outdoor activities during peak heat: If possible, restrict the chickens’ outdoor activities during the hottest parts of the day and allow them to roam when the temperatures are cooler.

Mist or sprinkle water in the area: Setting up a misting system or lightly sprinkling water in the chicken’s environment can help cool the air and reduce heat stress.

Monitor weather conditions: Stay aware of weather forecasts and plan ahead for extreme heat by implementing extra measures to protect the chickens.

Time feeding schedules: Consider feeding chickens during the cooler parts of the day to avoid additional heat generated during digestion.

Prevention is key to avoiding heat stroke in chickens. Being proactive and attentive to their needs during hot weather can significantly reduce the risk of heat-related health issues.

More Information